Ta strona dostępna jest również w polskiej wersji językowej

This is where we present articles, descriptions, and studies that concisely demonstrate microwave techniques and technology. We cover both theoretical and practical topics, complementing the technical information.

We describe microwave applications, including drying, heating, plasma generation, and supporting chemical reactions. We also explain the operation of microwave systems in Ultra High Vacuum (UHV) systems, at high temperatures, and in chemically aggressive environments.

MICROWAVES – BASICS OF SAFE OPERATION

Effects on living organisms

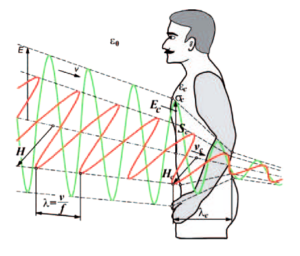

The effect of microwaves on the human body depends on the parameters of the electromagnetic field and the type of tissues. As the electromagnetic wave passes through the body, it transfers part of its energy. Tissues with high water content (e.g., muscles and blood) absorb the most energy.

The effect of microwaves on the human body depends on the parameters of the electromagnetic field and the type of tissues. As the electromagnetic wave passes through the body, it transfers part of its energy. Tissues with high water content (e.g., muscles and blood) absorb the most energy.

The primary mechanism of microwave interaction is thermal effects, i.e., a local increase in tissue temperature. The human thermoregulatory system distributes this heat throughout the body; however, the efficiency of this process is not the same for all organs.

Structures with poor blood circulation are particularly susceptible to thermal effects, including:

- the eye lenses,

- the urinary bladder,

- the testes,

- certain sections of the gastrointestinal tract.

The temperature rise caused by the electromagnetic field depends on:

- the field intensity,

- the frequency,

- the duration of exposure.

Occupational Health and Safety regulations in Poland

Until 2016, it was sufficient to observe the time spent in designated protection zones:

- unlimited time in the safe zone,

- up to eight hours in the intermediate zone,

- less than eight hours in the hazard zone (time depending on field intensity),

- prohibited access to the danger zone.

Based on the European Parliament and Council Directive 2013/35/EU of 2013, Poland issued the MRPiPS Regulation in 2016. Consolidated text: Dz.U. 2018 poz. 331, as amended. The user of the equipment is responsible, among other things, for:

- defining the boundaries of the protection zones,

- assessing hazards present in the area of field source operation,

- eliminating or reducing excessive hazards,

- training personnel.

The intermediate zone covers areas where the electromagnetic field may cause indirect effects, such as:

- disruption of electronic devices (including hearing aids),

- heating of implants (e.g., endoprostheses),

- malfunction of sensitive equipment.

Direct effects of electromagnetic field exposure may include:

- local tissue heating,

- pain,

- itching,

- muscle stimulation.

The hazard zone is an area where both indirect and direct effects of the electromagnetic field may occur.

The user is responsible for selecting protective measures appropriate to the specific situation. This is based on measurements of the electromagnetic field. In practice, the user may implement, for example, a specific method of workplace organization:

- designating and marking the area,

- introducing access restrictions,

- completely locking the room during equipment operation.

Limits of maximum field exposure

Protection zones generally have a complex spatial distribution of the field.

The Maximum Exposure Level (GPO) refers to the energy absorbed by tissues of the whole body or its parts (head, torso, limbs). GPO limits for the SAR (Specific Absorption Rate) are defined in Directive 2013/35/EU.

Based on measurements, it is possible to determine example exposure limits expressed in W/m²:

- IPNog-E – danger zone boundary: 150 W/m²

- IPNob-E – basic operational limit: 10 W/m²

- IPNod-E – hazard zone boundary: 1 W/m²

- IPNp-E – intermediate zone boundary: 0.1 W/m²

Final remarks

This document should be treated solely as a collection of information on potential hazards and ways to mitigate them. It is not a normative document and cannot be used as a basis for developing occupational health and safety rules or workstation instructions for operators of microwave equipment and systems.

This topic is covered in more detail during training sessions organized for users of equipment and systems purchased from MARKOM Microwaves

MICROWAVE DRYING OF BUILDINGS

Thermal transmittance (U‑value)

Moisture in building partitions has a direct impact on the building's energy efficiency.

A dry wall has a lower thermal transmittance (“U-value”), which means better thermal insulation. Since 2021, the U-value should not exceed 0.20 W/(m²·K). In energy‑efficient construction, the goal is to achieve U < 0.15 W/(m²·K).

Heat losses caused by moisture

Moisture in walls worsens the U-value. Heating a building with damp walls and foundations requires significantly more energy. In areas with high humidity, walls may be prone to frost damage. During severe frost, water in the wall can freeze, further reducing thermal insulation and potentially causing structural damage to the wall.

Wall insulation and moisture retention

In buildings where walls have been insulated with polystyrene, moisture cannot evaporate to the outside. This creates a kind of “thermos” effect. During the natural drying process, moisture evaporates into the interior of the rooms. In winter, rooms feel cold, and in summer, air can feel stuffy. Standard ventilation systems do not always solve this problem.

Wall moisture levels

Construction standards specify permissible moisture levels in walls. In practice, it is useful to know approximate values close to these standards:

< 3% – the wall is dry. This moisture level results from the normal use of the rooms. Reducing moisture below 3% is unnecessary from both an economic and practical perspective.

3–6% – slightly damp walls. To reduce humidity, it is usually enough to simply improve the ventilation system. Moisture levels should be periodically monitored.

6–10% – high moisture level. This is not just a matter of insufficient ventilation, so drying using dehumidifiers will be necessary.

10% – very damp walls. The cause of the moisture must be eliminated as soon as possible, followed by intensive drying.

Causes of moisture

There are many causes of moisture, and it is impossible to list them all. Some result from factors beyond the user’s control, others from neglect, and still others from unfortunate accidents.

Buildings constructed up to the mid‑20th century often lacked foundation waterproofing, so capillary rise of groundwater leads to persistent moisture in the foundations.

Damaged mechanical ventilation or uncleaned gravity‑ventilation ducts are common causes of elevated moisture levels in residential spaces.

Damage to water installations, broken gutters, or fire department interventions can locally cause a high degree of moisture.

Microwave drying of walls

There are many methods for effectively drying walls; below, one of them is discussed.

One solution is a Microwave Generator, specifically designed for drying walls. Such devices have been produced since 2012 by MARKOM Microwaves for construction companies and individual users.

Microwaves penetrate the wall structure, causing water molecules to evaporate. The water vapor escapes to the outside, allowing the wall to be dried throughout its entire cross‑section, while other methods only work on the surface.

As a result, microwave drying is 3–5 times faster—independent of wall thickness, moisture level, material, or surrounding conditions.

A detailed description of the technology can be found on the MARKOM Microwaves website.

Practical examples

Microwaves can be used to dry not only residential buildings but also industrial and agricultural facilities.

They are also effective in drying historic structures. Examples include the drying of monuments from the 1st century AD, such as Mensa Ponderaria, as well as sites listed as UNESCO World Heritage: Villa d’Este and Villa Adriana. This was described in the scientific journal Journal of Cultural Heritage, vol. 67 (2024).

The original article in PDF format is also made available by MARKOM Microwaves.

Microwave Magnetron Heads – the energy source in industrial systems

Industry, manufacturing, processing – in each of these areas, technological advantage determines competitiveness. Magnetron heads are a key component of systems based on microwave technology. They ensure controlled processing, regardless of the type or purpose of the production line.

Industry, manufacturing, processing – in each of these areas, technological advantage determines competitiveness. Magnetron heads are a key component of systems based on microwave technology. They ensure controlled processing, regardless of the type or purpose of the production line.

Microwave magnetron heads manufactured by MARKOM are used in various industries, including food processing, chemical, pharmaceutical, construction materials, and plastics processing. In many production lines, microwaves serve as the primary energy source, while the ability to adjust the microwave power allows precise alignment of parameters with the requirements of individual process stages.

Understanding the head’s construction helps to appreciate its impact on industrial processes.

The Microwave Magnetron Head is an electronic device that generates high-power electromagnetic waves in the microwave range. The most commonly used band in industry, science, and medicine is 2450 MHz ±50 MHz, which belongs to the ISM (Industrial, Scientific, Medical) frequency range.

The main components of the head are: the magnetron, the power supply, and the launcher (a short section of waveguide to which the magnetron is connected).

In MARKOM-produced heads, the magnetron operates at a single, fixed frequency. Despite its simple design, it is an exceptionally efficient source of microwave energy.

The pulsed power supplies used in the heads outperform traditional transformer-based power supplies. Their main advantages include:

- maintaining a stable magnetron power supply, independent of mains voltage fluctuations,

- monitoring and control of operating parameters,

- the ability to smoothly adjust microwave power.

The launcher, compliant with the WR340 or WR430 standard, transmits microwave energy from the magnetron to the device or industrial system.

Microwaves in technological processes enable:

- in the food industry – rapid and uniform heating while maintaining product quality, taste, and texture,

- in the chemical industry – uniform heating even of aggressive solutions,

- in pharmaceuticals – precise drying of substances, increasing process efficiency.

Adjusting the microwave power allows delivering exactly the amount of energy needed at any given moment. This directly translates into energy efficiency and reduced losses – an aspect particularly important in the context of global energy challenges.

Precision determines quality. Thanks to their versatility, they can be adapted to various technological processes.

Microwave magnetron heads are now an indispensable element of industrial systems where precision, efficiency, and flexibility matter. The use of adjustable microwave power increases process efficiency and stability, making production more sustainable.

Such flexible solutions, adaptable across diverse applications, have a tangible impact on the capabilities of current and future industry.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF UNITS IN VACUUM TECHNOLOGY

In many fields, measurements of the same physical quantity are recorded using different units. Sometimes this is justified by historical factors, and in many cases it results from practical needs. The SI system is officially used. In practice, however, other units can also be encountered. A good example is distance; here are a few selected units:

In many fields, measurements of the same physical quantity are recorded using different units. Sometimes this is justified by historical factors, and in many cases it results from practical needs. The SI system is officially used. In practice, however, other units can also be encountered. A good example is distance; here are a few selected units:

- meter [m] and its multiples: [µm] – precise CNC machining, [km] – cartography

The meter was introduced in the 18th century as part of the French reform of the measurement system to create a universal unit based on the dimensions of the Earth. - inch [in]: used not only in Anglo-Saxon countries, in reference to pipe diameters and thread pitches. It originates from the imperial system; its length was originally based on the width of a human thumb.

- nautical mile [NM]: distance measured at sea. It originates from dividing the Earth into degrees of latitude – one nautical mile corresponds to one minute of latitude arc.

- astronomical unit [AU]: used to measure distances within our solar system and beyond. Introduced in the 20th century, originally defined as the average distance from the Earth to the Sun to facilitate astronomical calculations.

- light-year: the distance light travels in one Julian year (365.25 days), used in astronomy to express distances between stars or galaxies. The concept emerged in the 19th century along with the development of the theory of the speed of light and the need to express vast distances in space.

It can be observed that industry, cartography, and astronomy need to use different units for measurement. Converting everything to the SI system would not only create confusion and misunderstandings, but it would also be practically useless.

A light-year is approximately 9.5 trillion (9.5 × 10¹²) kilometers, or 9.5 × 10¹⁵ meters. While this can be expressed mathematically, using such a notation is practically meaningless. Moreover, measuring such vast distances with an accuracy of one meter is unnecessary.

Pressure units

Since the 17th century, scientists have been trying to understand the nature of pressure. Torricelli constructed the first mercury barometer. In his honor, the pressure unit Torr was named in the 20th century.

In the 19th century, the Pascal unit was introduced – precisely defined in the SI system. In industry, more practical units became widespread. To this day, both “scientific” units (Pa) and “technical” units (bar, atm) coexist, and in vacuum technology, the Torr is commonly used.

Pascal [Pa] is an SI unit defined as 1 N/m². In physics and metrology, it serves as a fundamental reference unit, but in practice it is rarely applied in its pure form, especially in the context of vacuum, where values are very small and more convenient scales are needed.

Millibar [mbar] is a convenient scale used in meteorology and vacuum technology. It allows easy description of pressures ranging from atmospheric pressure down to medium vacuum levels. Simultaneously, the use of the hectopascal [hPa] is also common. The choice between mbar and hPa is often a matter of habit and tradition.

Torr is a unit historically associated with vacuum research. Today, the Torr is still widely used in vacuum physics and laboratory technologies because it allows an intuitive reference to vacuum levels relative to atmospheric pressure.

The choice of unit is determined not only by mathematics but also by practice, tradition, and the intuition of specialists.

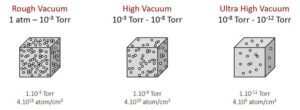

Ultra hugh vacuum (UHV)

The imprecise term “vacuum” refers to sufficiently low residual pressure remaining after air is pumped out of a chamber. The classification of vacuum types is conventional and depends on the residual pressure value. Pressures on the order of 10⁻¹⁰ mbar, or 7.5 × 10⁻¹¹ Torr, already correspond to ultra-high vacuum (UHV). Such low pressures are required in surface physics, spectroscopy, and the operation of particle accelerators.

To clarify the significance of low pressures for advanced technologies, for the purposes of this article, all pressure values in the following sections will be given in Torr.

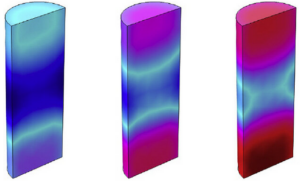

The quality of a vacuum, expressed in Torr, indicates the level of residual pressure. In plasma systems, such as a stellarator, all air is pumped out of the process chamber. This is necessary because air molecules interfere with the ignition and maintenance of a stable plasma.

Striving for the ideal, an ultra-high vacuum (UHV) is achieved, with levels ranging from 10⁻⁸ to 10⁻¹² Torr. However, approximately 10⁶ molecules remain in each cm³ of the chamber. This is an extremely small number. For comparison, air at atmospheric pressure contains about 2.5 × 10¹⁹ molecules/cm³.

Plasma in a vacuum

A controlled amount of gas is introduced into a chamber under UHV conditions. The quantity depends on many factors, but it can be assumed to be in the range of 10¹⁰–10¹² molecules/cm³.

The gas introduced into a stellarator can be hydrogen, its isotopes (deuterium or tritium), helium, argon, neon, or krypton. In these gases, electron ejection is relatively easy. To achieve this, energy must be supplied to the gas, either by heating it, directing a laser beam at it, or using microwaves.

The electron has a negative charge. An atom without its electron becomes a positively charged ion. With such a small number of particles, the distance between the particles is very large. The ejected electron remains in the space between atoms. The resulting mixture of ions and electrons forms a plasma.

After the plasma is ignited, maintaining stable vacuum conditions is essential. Any additional air molecule can locally cool the plasma, causing instability and, ultimately, extinguishing it.

When designing a complex vacuum system such as a stellarator, the tightness of all vacuum chamber components must be taken into account. A parameter used to assess tightness is Torr per minute, which indicates how many air molecules enter the stellarator in one minute. It may also indicate that the vacuum pump performance is too low. Measuring leaks or considering them in process analysis is crucial information for both the designer and the system operator.

An example of components used in stellarators are waveguides and vacuum windows produced by MARKOM.

This links the level of vacuum to the number of molecules remaining in the chamber as well as the number of molecules entering through leaks. This is critically important in highly advanced technological processes. Controlling the number of molecules determines the success of the entire process and the stability of the plasma.

MICROWAVE DRYING UNDER REDUCED PRESSURE

Introduction

Microwave drying, especially microwave drying at reduced pressure, is still relatively unknown to the general public. The performance of such microwave devices (vacuum dryers) is the key factor in deciding whether to implement this technology.

A comparison of drying methods will indicate which one can shorten processing time and reduce energy consumption in many industrial applications.

Water Bonding in Materials

The principle of microwave interaction with water molecules is widely known. In a microwave field, the molecules begin to oscillate in response to changes in the field. These oscillations generate heat, raising the water temperature until it boils and evaporates.

There are three ways of binding water in a material:

- Surface: water remains on the surface of hygroscopic materials,

- Capillary: water is contained in capillaries (thin tubes),

- Molecular: water is bound to the material’s molecules.

Unlike other methods, microwave drying can effectively dry almost all materials and products, including those sensitive to high temperatures when drying under reduced pressure.

Microwave Drying

To estimate the performance of an industrial microwave system during the water evaporation process, theoretical calculations can be used.

Assuming the energy source generates microwaves with a power of 1 kW, this power is equivalent to 1 kJ/s.

The unit of latent heat is kJ/kg. For water, this value is 2433 kJ/kg.

The evaporation rate of water is determined by the ratio of latent heat to supplied energy. This means that evaporating 1 kg of water using a 1 kW energy source will take 2433 seconds, or about 41 minutes.

An important factor is that microwaves penetrate the dried material and supply energy simultaneously throughout its entire volume. There are also no technical obstacles to carrying out the drying process in a reduced-pressure chamber.

At reduced pressure, the boiling temperature of water is lower. Therefore, less energy is required for the water to start evaporating. By lowering the pressure in the chamber, the evaporation time of 1 kg of water, using a 1 kW energy source, is even shorter.

Hot air drying

Drying with air is obviously difficult to achieve under reduced pressure. In this comparison, we will therefore assume drying occurs at normal atmospheric pressure.

The air supplied for drying has a relative humidity of 0% and a temperature of 60 °C (40 °C above ambient temperature), with a flow rate of 100 l/min.

Heating 100 liters of air by 40 °C in one minute requires approximately 0.08 kW of power.

Upon contact with the cooler dried material, the air temperature drops. Nevertheless, it becomes fully saturated (reaching 100% relative humidity).

At a lower temperature, the air absorbs about 10 g of water per minute. Over 41 minutes, approximately 410 g of water will be removed.

Comparison of Results

In 41 minutes of microwave drying, 1 kg of water is evaporated. In the same time, hot dry air evaporates only about 0.41 kg of water. Thus, microwave drying evaporates more than twice the amount of water.

The energy demand for microwaves during 41 minutes is 0.68 kW. In the same time, heating the air requires 3.28 kW. Therefore, the energy demand of microwaves is more than four times lower.

Practical examples

An experiment was conducted by GEA involving the drying of lactose (milk powder). Tanks with capacities ranging from 10 to 1200 L were used.

To remove 1 kg of water using microwaves with a power of 2.4 kW, approximately 40 minutes were sufficient, regardless of the tank capacity.

In the case of hot air drying at a temperature of 60 °C, with a flow rate of 100 L/min, removing 1 kg of water required between 120 and 270 minutes. In this case, tank capacity had a significant impact.

Other projects have also been realized, demonstrating the real capabilities of microwave technology in this field. One example is Project No. FP6-513205 POLYDRY, “The Development of an in-line energy-efficient polymer microwave-based moisture measurement and drying system.”

Conclusions

Many aspects related to the evaluation of the effectiveness and efficiency of microwave drying systems and hot air drying systems have not been included here.

Even if we assume that the actual difference in efficiency between these two systems is 50% smaller, the microwave system still holds a significant advantage.

The information and comparisons presented allow potential users to assess whether a solution based on microwave technology will find application in their system.

Smooth Microwave Power Regulation – Precision in Industrial MARKOM Microwave Systems

In industrial settings where efficiency and precision are paramount, accurate magnetron power control has become essential. This capability plays a crucial role in processes such as drying, heating, and curing. At MARKOM, we understand this need deeply, which is why we supply microwave systems that allow fine-tuned power adjustment. Such solutions offer full process oversight and real energy savings.

In industrial settings where efficiency and precision are paramount, accurate magnetron power control has become essential. This capability plays a crucial role in processes such as drying, heating, and curing. At MARKOM, we understand this need deeply, which is why we supply microwave systems that allow fine-tuned power adjustment. Such solutions offer full process oversight and real energy savings.

Power Control Methods

In the past, users adjusted power by changing the conduction angle of each half-cycle of current—using thyristors or triacs. This method suffered from low efficiency, limited accuracy, and considerable electrical noise. Today, it is considered obsolete.

The standard approach now uses Pulse-Width Modulation (PWM). A microprocessor controls the magnetron supply voltage, dividing it into a series of rectangular pulses. By varying the pulse width (duty cycle), the output microwave power is adjusted. This method reduces electrical noise and ensures repeatable performance.

MARKOM incorporates impulse power supplies with smooth power regulation in its products (magnetron heads, microwave generators). Microwave power can be set in two ways:

- Analog Control: via control voltage (0–5 VDC or 0–10 VDC), proportional to the desired microwave output.

- Digital Control: via RS 485 using the Modbus RTU protocol, with each power supply uniquely addressable.

Key Applications

The benefits of smooth power regulation are evident in specific applications. Our solutions, such as the MMH magnetron heads and MG microwave generators, exemplify this:

- Food Industry

Precise power control prevents localized overheating, ensuring even thermal processing. The result: higher product quality, optimal energy use, and customer satisfaction. - Pharmaceutical Industry

In drying active ingredients or heating mixtures, smooth power regulation ensures ideal process conditions. This is the key to preserving the properties of active substances. - Chemical And Construction Industries

From controlled curing of resin adhesives to uniform paint drying, smooth power regulation ensures materials achieve the required performance parameters: appropriate strength, durability, and other properties critical for the specific application.

Benefits Of Power Control

Energy And Cost Savings

Power is matched to actual process needs, eliminating waste and preventing process errors—leading to lower production costs.

Protection Of Sensitive Materials

Adjustability prevents material damage, boosting final product quality.

Sustainability

Optimizing energy use supports environmental goals. This also enhances brand image. Implementing microwave systems with smooth power regulation can be a compelling argument in applications for grants supporting energy efficiency and sustainable development.

Conclusion

Smooth microwave power regulation is crucial for competitive industrial production—provided the system is properly designed, application-specific, and ensures full control over process parameters.

Explore real-world examples on LinkedIn and in the Applications section to see how our technology performs in action.

Elimination of Wood Pests Using Microwaves

Innovative Technology for Protecting Wooden Heritage

Innovative Technology for Protecting Wooden Heritage

Wood, harvested from felled trees and stripped of bark, is a widely used construction material vulnerable to pest attacks. Their activity can cause serious damage to historic wooden elements, building structures, and furniture.

Deathwatch Beetles and House Borers – Key Threats to Structural Wood

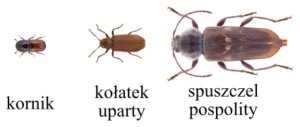

It is often mistakenly believed that Bark beetles (Ips Spp.) are responsible for wood damage; in reality, the primary threat comes from the Common Deathwatch Beetle (Anobium punctatum), Steadfast Deathwatch Beetle (Hadrobregmus pertinax), and European House Borer (Hylotrupes bajulus). The Common Deathwatch Beetle is a small beetle (about 3–5 mm long) whose larvae feed inside both coniferous and deciduous wood, especially in structural timber. The Steadfast Deathwatch Beetle (about 4–6 mm long) attacks construction timber from coniferous species such as spruce, fir, pine, and larch. The European House Borer is significantly larger (about 15–25 mm) and primarily infests softwood structural elements like roof trusses, beams, and framing.

It is the larvae of these insects that tunnel through the wood, causing characteristic scraping and tapping sounds. A visible sign of their activity is wood shavings falling out from exit holes.

Microwaves in the Service of Protecting Wooden Heritage

Traditional methods for controlling wood pests, such as chemical treatments or gases, are invasive and not always effective. An alternative is microwave treatment for wood pests, which involves heating the wood to temperatures above 55 °C. This process causes denaturation (i.e., permanent damage to the protein structure) of the pests, effectively eliminating them. Microwaves penetrate deep into the wooden element without damaging its structure, making this method safe both for the material and the environment. Users of our microwave systems from many countries are aware of these benefits. In the Projects section, we showcase our implementations for both Polish and international clients.

Use of Microwave Generators

Using these Microwave Generators makes it possible to eradicate larvae and insect eggs without risking damage to the wood. This technology is applied in heritage conservation, protection of wooden structures, and removal of pests from furniture and other wooden elements.